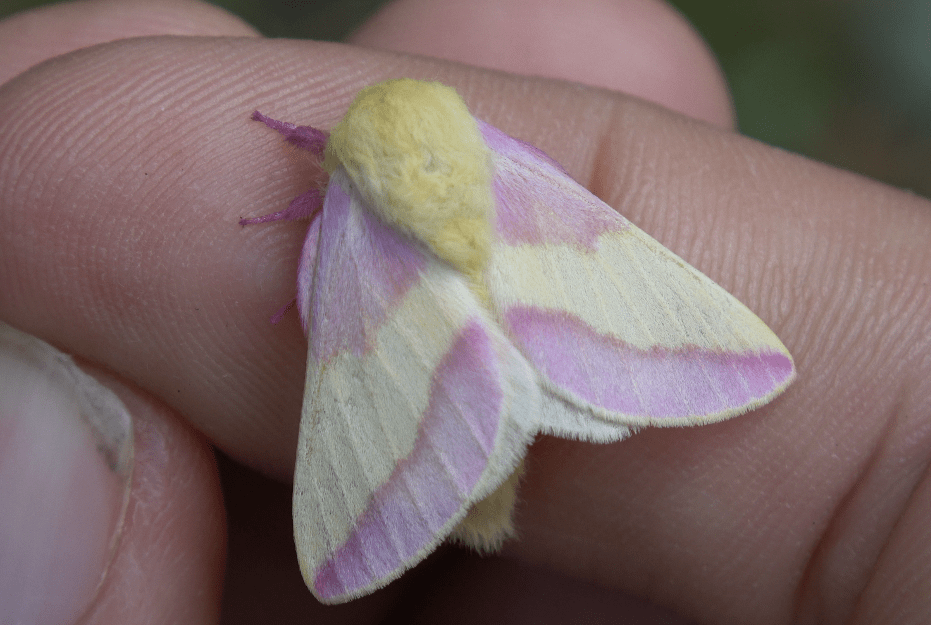

The Rosy Maple Moth or Dryocampa rubicunda is an iconic species of moth; their remarkable pink and custard yellow colors have brightened many people’s day! As the name suggests, the species is strongly associated with it’s primary host plant: Acer sp. or maple on which the larvae feed. The species is found in the Eastern U.S.A – Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, eastern Texas, eastern Nebraska, eastern Kansas, Arkansas, Missouri, Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Virginia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire but also in Canada (Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, , Canada – generally southeastern Canada that connects to the U.S.A border, near Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal).

The larvae of rosy maple moths primarily feed on – you guessed it – maple tree. Many kinds of maple tree, in fact. (in the wild larvae were recorded on: Acer monspessulanum, Acer negundo, Acer pseudoplatanus, Acer rubrum, Acer saccharinum, Acer saccharum, Acer spicatum and more). But a lesser known fact is that the larvae can and do also feed on oak tree (!) in the wild (Quercus coccinea, Quercus ilicifolia, Quercus laevis, Quercus nigra, Quercus velutina). It is possible that oak tree is a secondary, ‘ancestral’ host plant for this species (rosy maple moths are in fact closely related to striped oakworms, or genus Anisota). Some reports mention that the larvae have a lower survival rate on oak tree compared to maple although I still have to verify the veracity of this claim; but is it not unheard of for moths to have a ‘primary’ host plant and a ‘secondary’, suboptimal host plants that they might use if their main preference happens to be less available.

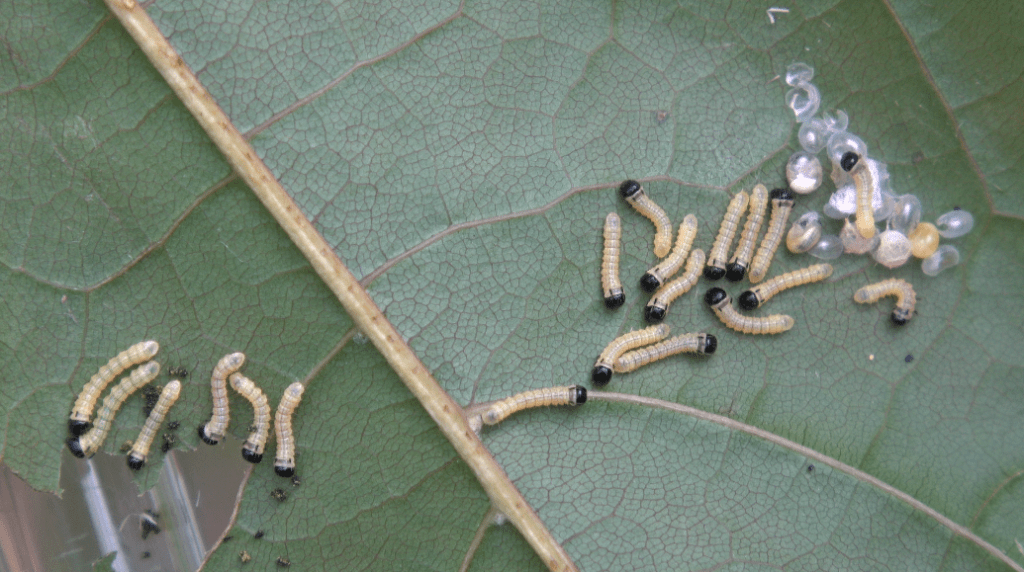

The larvae of the rosy maple moth are a little bit variable; but generally speaking they are a creamy white-ish green to a more lime-green. They have dorsal stripes that run along their whole body; these stripes also vary in color and they can be green, grey or black. The head capsule is orange (or black in younger larvae). The larvae of rosy maple moths are very social and feed in groups for the first three (until L3) life stages. In L4, groups of two or three can be seen feeding together, but they become more solitary and disperse. And in the final instar (L5) the caterpillar becomes totally solitary. They have two thoraric setae that from a distance almost have the superficial appearance of ‘antennae’.

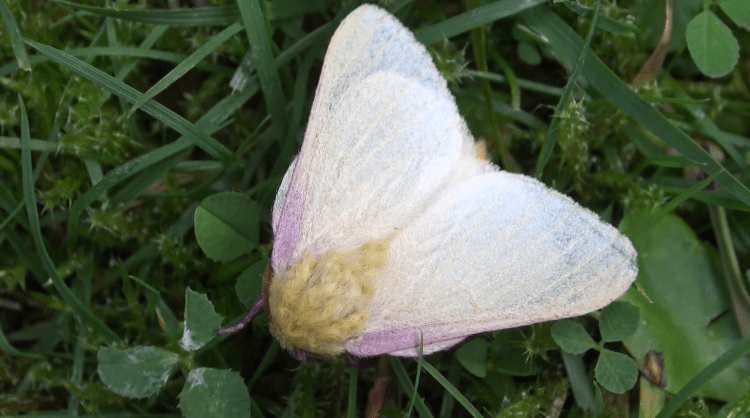

Not always rosy: The species is famous for being pink; but in reality not all of them are pink! The species has lighter colour forms too. This form is often referred to as rubicunda ‘alba’ and while it can occur anywhere it seems to be the most common near Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska and Ontario, Canada. Some individuals can have pure yellow wings in some cases! Intermediate forms also exist, where the surface area of pink scales is greatly reduced. So do not be surprised or even disappointed if you raise caterpillars of this species and they just so happen to transform into yellow or even white-ish moths instead of the pink ones you were anticipating! And even in pink individuals the ‘pinkness’ seems to vary; the shade of pink is more intense on some individuals than on others.

Sometimes, moth fanatics and bug lovers raise this species in captivity for fun. It is highly recommended, since A) it is a very widespread and common insect, so it will do their conservation no harm! B) they look simply adorable C) since they are small, the caterpillars and moths don’t use a lot of time and resources D) the caterpillars and moths are harmless; they are not venomous or poisonous in any life stage E) although probably not the best beginner species, they are also not terribly hard to breed F) having close experiences with insects benefits their conservation and makes us care about them more; ignorance is an existential threat to insects! In fact, me, as the author of this website, have started my interest in entomology when I was a child, after rearing local caterpillar species into moths and being amazed by the process. Now several decades later I have one of the biggest websites on the internet about moths, written all by myself! Therefore, like all the other pages on my website, this article also contains a caresheet for how to breed this species yourself.

- Difficulty rating: Average (Not the easiest but not hard. But you will need Acer sp.!)

- Rearing difficulty: 5.5/10 (From egg to pupa)

- Pairing difficulty: 3/10 (Achieving copulations)

- Host plants: Maple, or Acer sp. – Acer saccharum preferred plus Acer pseudoplatanus, rubrum and saccharinum are also recommended. In the wild larvae have been found on Acer monspessulanum, Acer negundo, Acer pseudoplatanus, Acer rubrum, Acer saccharinum, Acer saccharum, Acer spicatum and more. The larvae can also feed on oak tree. Recorded in the wild are: Quercus coccinea, Quercus ilicifolia, Quercus laevis, Quercus nigra, Quercus velutina. and perhaps more.

- Natural range: Eastern U.S.A (Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, eastern Texas, eastern Nebraska, eastern Kansas, Arkansas, Missouri, Michigan, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Virginia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire) but also in Canada (Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, , Canada – generally southeastern Canada that connects to the U.S.A border, near Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal).

- Polyphagous: Yes, but not very, they are picky eaters. It is more of a specialist that feeds on maple tree [Acer sp.] – they are also reported to eat oak in the wild and in captivity [Quercus] but with bad result. It will try to feed on most species of Acer sp., but it prefers Acer saccharum.

- Generations: Univoltine to multivoltine – usually only one generation a year, second generation and even third generation is possible in captivity and in warmer years in the wild. There seems to be plasticity to the life cycle depending on the local conditions.

- Family: Saturniidae (silkmoths)

- Pupation: Subterranean (burrows in soil)

- Preferred climate: Temperate. Cooler to warmer summer temperatures and a cold winter

- Special notes: The first instars require very high humidity and are very sensitive to drying out. The final instars seem to be the opposite, too high humidity makes them sick.

- Wingspan: 15 – 35mm (Very small for Saturniidae)

- Binomial name: Dryocampa rubicunda (Fabricius, 1793)

Dryocampa rubicunda is not difficult to breed in my (subjective) opinion. However, it is easy to make mistakes while breeding them, since what the larvae require is a little counterintuitive. After breeding this species several times, I have come to the conclusion that the young larvae (instar 1 and 2 especially) require the highest degree of humidity. This means closed, airtight plastic boxes with no ventilation. They also need fresh leaves every 1-2 days. It seems that when exposed to indoor rearing conditions they are vulnerable to drying out. However, as the larvae grow bigger, they exponentially start to require a more dry and ventilated environment. For example, the final instar (L5) I typically keep in a completely open setup; net-cages with branches of food plant in water that they can free roam on. Fully grown larvae seem to get sick easily when exposed to high humidity all the time. Basically, in terms of humidity the species goes from one extreme end of the spectrum to the other end. This is where some insect breeders might fail! However, knowing this information beforehand makes the process much easier and hopefully this website will spare you the trial-and-error part others had to go through.

The eggs of this species hatch in about two weeks (14 days) near room temperature (20C) although it seems that warmth can significantly speed up this process. I’ve had eggs hatch in as little as about 7 days during a hot summer. They can be incubated in a plastic petri dish or airtight container. Keep the humidity higher by soaking a small piece of paper towel in water, roll it into a humid little ball, and place it in the container with the eggs. I prefer using this method over spraying the eggs, since the eggs and baby-larvae are extremely small. They are so small that they can drown(!) inside a droplet of water. So if you do decide to spray the eggs, make sure you use a very fine plant mister and make sure no condensation will form.

To raise this species succesfully, Acer sp. (maple) is required. Literature mentions oak (Quercus), but the species seems to rarely use this plant in the wild, so it’s probably not their main preference. I have raised them with good results on Acer platanoides and Acer pseudoplatanus. I am not sure if some species of Acer yield a better result than others; it might be possible but it requires some testing – however, the species seems to do reasonably well on most Acer species. Most often consumed by the caterpillars in nature are red maple (Acer rubrum), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), and silver maple (Acer saccharinum) so using these is probably a good idea too.

Instar 1 (L1) to instar 3 (L3): Make sure to rear them inside plastic boxes. Give the first two instars (L1-L2) little to no ventilation. Do not keep them in wet conditions. But do keep them in humid conditions! The small larvae are very sensitive to drying out. Give them very fresh leaves and make sure to replace the maple leaves every 1-3 days if you can. If you make it through the first instars, the rearing becomes more easy eventually, I promise.

The first three instars typically feed, travel and moult in groups. It seems that these social larvae grow and develop better in higher numbers. Make sure to obtain enough eggs; groups with more than about 15+ larvae (the number is arbitrarily chosen of course) do seem to feed and grow slightly faster.

In the fourth and fifth instar, their behavior suddenly changes. Now the the larvae will gradually become more solitary. In L4, the larvae can still be seen feeding in smaller groups, usually 1 to 5 larvae feeding in the same vicinity, so I suppose they might be semi-social still in L4, but they definitely display a strongly diminished tendency to form groups compared to earlier instars. Then finally, in L5 or the ‘final’ instar, they disperse and become completely solitary. When this happens, they become more intolerant when it comes to overcrowding and high population densities. Whereas you can safely place high numbers of young larvae within one container, the fully grown larvae don’t seem to appreciate overcrowding, as they now need more personal space per larva!

Another change is the fast that (in my opinion) the L4 and L5 larvae prefer to be more dry and ventilated. Compared to L1-L2-L3; the L4-L5 larvae tend to get sick if faced with constant high humidity, stuffy conditions or a lack of ventilation. They can be reared in pop-up insect cages, IKEA laundry baskets, or in boxes with the lid removed (add netting) in an open to semi-open more dry setup. Offer them branches of food plant in water.

One fully grown (in 1.5 to 2 months) the larvae will descend to the floor and attempt to burrow. This ‘silkmoth’ (Saturniidae) species (like many others from the Ceratocampinae subfamily) does not spin cocoons, but instead, larvae burrow underground and pupate there.

In captivity, pupating larvae can be provided shredded paper towels in order to pupate safely. They’ll also pupate in (fine) vermiculite and other substrates.

So when will you see the moths? Ah. That depends on the season. Dryocampa rubicunda has one to three broods a year, it seems. In colder years, especially in the far north they might have as little as one brood – two broods if conditions are acceptable. But as it gets warmer (for example south of the Carolinas) they can have two or three broods a year. You see the larvae and the pupa* decide if hibernation is in order or not. If the temperatures are higher and the number if daylength hours is increasing they may decide to produce another brood. In cooler, darker conditions they might decide to hibernate. It’s hard to predict what happens in captivity since here they receive different cues than they would in nature! You can also help them hibernate by storing the (fresh) pupae cold. Generally speaking, larvae reared late in the year (late September, October, November) are inclined to go and hibernate as pupae.

*= yes, the species hibernates as pupae, not as larvae. But the choice to hibernate (or not and develop into a moth instead) is not exclusively made by the pupae, but also by the conditions the larvae are reared in. Factors such as temperature, but also daylight hours (daylength) play a role.

Generally speaking I store the pupae outdoors when it becomes chilly or cold outside (October to late April usually), which seems to induce hibernation. Before that, between late April and October, I store them indoors on room temperature. It is best to follow the seasons for temperate species. If your pupae do decide to develop, expect moths in about 1-2 months or so. If hibernating store them cool until spring.

The pupae have a rough texture (almost like sandpaper) and also have tiny spikes. They can wiggle slightly in some cases, if disturbed. An easy to improvise emergence box is shredded paper towel or vermiculite, kept slightly moist.

If you’ve done everything well so far then expect to see gorgeous, pastel colored pink (or yellow!) forest-fairies. Congratulations!

Unfortunately the moths are not very long lived. Females live for about 9 to 14 days or so. Males are much shorter lived; they expire in 4 to 8 days usually.

Pairing this species is not super difficult. The moths are generally very eager to mate, but there is a catch! It seems that males don’t live very long. In captivity, the males also tend to lose their tarsi (the ‘claws’ on their legs) after 3-4 days in some cases, making it difficult to grasp the female. And if unmated, females will grow impatient in some cases and start to lay their (infertile) eggs.

What this means is that you ideally need ‘fresh’ males and females (not older than 3 days) to get pairings. While older individuals are capable of mating in some cases, their chances of doing so dwindle rapidly. The unfortunate thing here is that as a moth breeder, it’s not really possible to control when exactly certain individuals emerge from their pupae. But the goal here is ideally to have a male and female emerge on the same day (or 1-2 days apart from each other) to maximize your chances of success. Unfortunately this comes down to sheer luck; however, the probabilities and odds can be increased in your favor by raising a higher number of individuals. The good news is broods tends to emergence in a synchronized way and not too sporadically. So if you raise a dozen or so individuals, there’s a good chance that the lifespan of some males and females overlaps. – Older females seem to be much more capable of mating than older males, though, so it mostly comes down to having a ‘fresh’ male available.

That being said, if these conditions are met, the moths generally tend to mate very easily. Males are eager to approach females and they often immediately mate with one the very first night. The species is nocturnal, and they are best left in pop-up cages or laundry baskets in a dark place with no artificial light. Some airflow can be beneficial too. Males and females tend to stay connected for several hours when mating. However, males do have a tendency to leave the females before dawn in a lot of cases, so the ‘morning-after’ it’s not always clear if your moths have mated last night. It’s easy to observe at night though. The moths seem to be tolerant of cooler temperatures.

When it comes to laying eggs females are not picky at all (like most Saturniidae) and in captivity females will just randomly lay and scatter the eggs on the walls of their enclosure (in nature she’d lay them on the leaf or bark of a maple tree).

Thank you for reading this article! I hope it was useful. Thank you to all my readers, sponsors, patrons and contributors! This page was revised (22th October, 2025) to become a higher-quality version of itself. Slowly I will revise all the old and outdated pages on this website.

Notes on sleeving: ‘Sleeving’ is a rearing method on which a moth breeder lets the larvae ‘free roam’ on a living plant, usually outdoors, contained inside of a bag called a ‘rearing sleeve’. This method seems to work reasonably well for Dryocampa rubicunda, if sleeved in a place where they are not exposed to direct sunlight and constant rain.

Thank you for reading my article. This is the end of this page. Below you will find some useful links to help you navigate my website better or help you find more information that you need about moths and butterflies.

Dear reader – thank you very much for visiting! Your readership is much appreciated. Are you perhaps…. (see below)

- Not done browsing yet? Then click here to return to the homepage (HOMEPAGE)

- Looking for a specific species? Then click here to see the full species list (FULL SPECIES LIST)

- Looking for general (breeding)guides and information? Then click here to see the general information (GENERAL INFORMATION)

- Interested in a certain family? Then click here to see all featured Lepidoptera families (FAMILIES)

Citations: Coppens, B. (2025); Written by Bart Coppens; based on a real life breeding experience [for citations in literature and publications]

Was this information helpful to you? Then please consider contributing here (more information) to keep this information free and support the future of this website. This website is completely free to use, and crowdfunded. Contributions can be made via paypal, patreon, and several other ways.

All the funds I raise online will be invested in the website; in the form of new caresheets, but also rewriting and updating the old caresheets (some are scheduled to be rewritten), my educational websites, Youtube, breeding projects, the study of moths andconservation programs.

Donate button (Liberapay; credit card and VISA accepted)

Donate button (PayPal)![]()

Become a member of my Patreon (Patreon)![]()

Find me on YouTube

Find me on Instagram![]()

Join the Discord server: Click here

Join the Whatsapp server: Click here

Facebook: Click here