Mexico has a wonderful and biodiverse landscape – its wide variety of habitats, climate types and it’s various mountain ranges have the tendency to form geographical barriers for the populations of organisms. These organisms, in reproductive isolation, then diverge and can eventually evolve into seperate species.

Copaxa parvohidalgensis is one such species – it’s part of a group of very similar looking moths, namely the widespread moth Copaxa lavendera (Mexico to Nicaragua presumably) that upon closer inspection appears to be not just one species, but several cryptic species -described more recently are Copaxa lavenderoguatemalensis (Guatemala), lavenderohidalgensis (Hidalgo), lavenderojaliscensis (Jalisco), parvohidalgensis (Hildago), lavenderohondurensis (Honduras).

This medium size silkmoth is very colorful; it seems to have bright orange males and yellow-brown females.

Taxonomy is a complicated thing; and it does not help that overzealous taxonomists nowadays are often more concerned about slapping their name on a new species, rather than trying to understand the organism.

Not much information is known about Copaxa parvohidalgensis; it seems to be one of the of the species that was recently split – off from Copaxa lavendera. The type locality appears to be Hildago, in Mexico. I am an amateur entomologist that enjoys rearing moths in his spare time, and I was provided a few eggs off this emperor moth for my personal entertainment. It appears that almost no life history information is available for this species, and the pictures and information I have gathered while rearing this species in captivity, is currently some of the only available information that one will find about this species online.

Rearing species can provide us with valuable information however. Because sometimes, it is very hard to tell the difference between two similar species; in some cases, it’s only possible to know the difference between two species by dissecting them or taking DNA samples. However, suprisingly, while two moth species may look similar, their larvae may look radically different, betraying the fact that they are after all different species.

Such is the case with Copaxa parvohidalgensis. I was provided eggs of this species under the presumption that they are Copaxa lavendera. However, having reared Copaxa lavendera myself in the past, I quickly noticed differences in the larval stage.

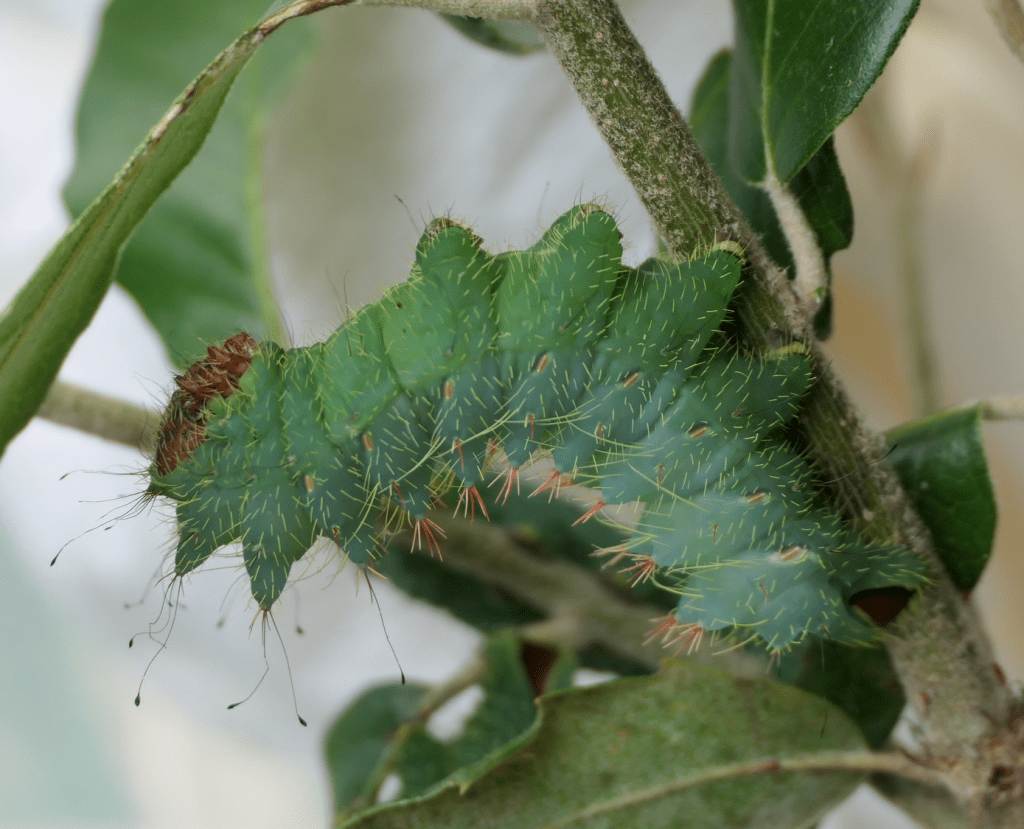

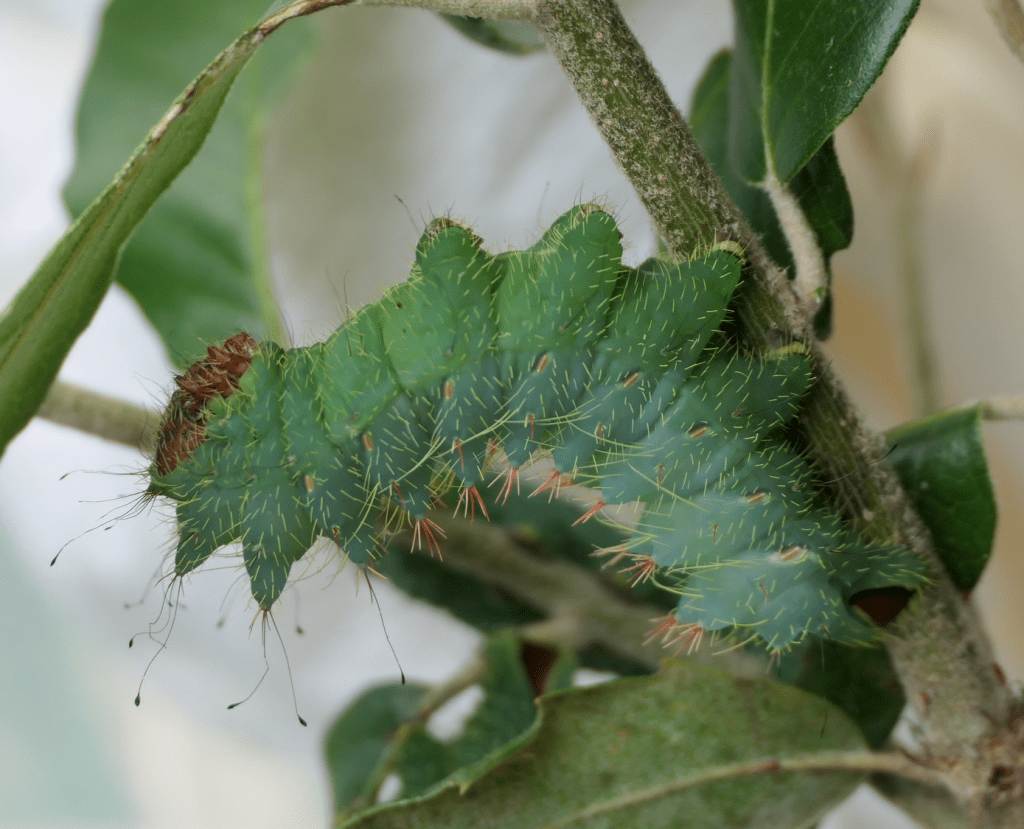

The larvae of Copaxa parvohidalgensis have an unusual blue-ish shade; I can only describe it as something in between mint-green or cyan.

No information is known about their host plant in the wild; but it’s more widespread cousin, Copaxa lavendera, is said to feed on Lauraceae (Persea) and Fagaceae (Quercus) in the wild. Therefore, I provided them several species of oak tree (Quercus) in captivity; the larvae grew well on them. In captivity it appeared to produce two broods; the second brood hibernating. If the same happens in the wild, I cannot say; sometimes moths behave differently in captivity. But it is likely that it produces 2 to 3 broods before diapausing as cocoons, like most (but not all) central-American Copaxa species. The larvae appeared to like moderate to warm (18-25C) temperatures and moderate to humid (RV 60%-80%) humidity.

The species is not difficult to rear it seems, although basic experience with moths is warranted, due to the fact there is little information about them online (well, before I wrote this article that is), and one must be able to make accurate conjectures in order to raise species of which little information is available.

- Difficulty rating: Average – not hard to breed but basic experience is recommended

- Rearing difficulty: 6/10 (From egg to pupa)

- Pairing difficulty: 5.5/10 (Achieving copulations)

- Host plants: Mostly unknown; in captivity they have been shown to eat a variety of Quercus sp. (Fagaceae). It is unclear to me what the larvae feed on in the wild. Like other species from this group, there is a probability they use Persea sp. (Lauraceae) in the wild.

- Natural range: Hidalgo, Mexico

- Polyphagous: yes (presumably), I reared them on a variety of Quercus (Q. ilex, robur and suber). They eat both deciduous and evergreen oak in captivity.

- Generations: Unconfirmed in the wild(?). In captivity they appeared to produce two broods without diapausing. Other breeders have managed to diapause additional broods by keeping cocoons cool; while some have managed to continuously breed them by keeping cocoons warm (room temp).

- Family: Saturniidae (silkmoths)

- Pupation: Cocoon (silk encasing)

- Preferred climate: It is not precisely known to me what climatic conditions prevail in the (micro)habitat of this species. However, the state in Mexico where it occurs, Hidalgo, is described as ‘hot, cloudly, windy and humid’ with a ‘very short but dry, cool winter’. In captivity, the species does well in room temperature or higher. (21C+).

- Special notes: Not often reared; but breeding is similar to the more frequently reared Copaxa lavendera (Westwood, 1854).

- Estimated wingspan:

- Binomial name: Copaxa parvohidalgensis (Brechlin & Meister, 2010). Warning: this is a Brechlin & Meister species (Click here for details!).

The eggs of Copaxa parvohidalgensis are somewhat oval in shape; they have a chocolate brown center, and a creamy white ring runs around the circumference of the slightly oval egg. The development time on room temperature was close to two weeks (12-15 days). Pale, yellow larvae hatch from the eggs. The first life stage appears to be gregarious; the larvae form little groups and feed together.

Eggs can be incubated in petri dishes – and larvae from instar 1 to instar 3 (L1 to L3) can be reared in plastic boxes lined with tissue paper and large ventilation holes drilled into them; they do prefer moderate airflow.

The first two life stages are social in nature and form small groups; the third life stage becomes solitary in nature. In captivity the species was easy to breed in plastic boxes provided they have adequate ventilation (large ventilation holes were cut in them and covered with mesh). Larvae were fed a variety of Quercus; including Quercus suber, Quercus ilex and Quercus robur.

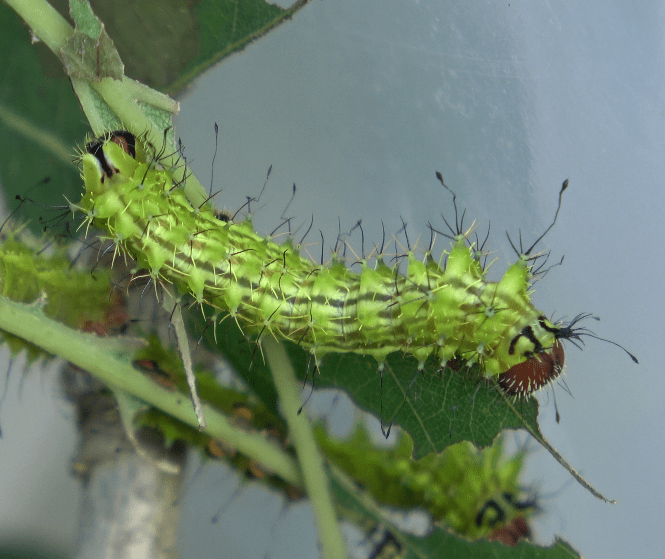

The third, fourth, and fifth live stages can be kept in large plastic boxes provided there is a adequate ventilation, moderate humidity, and a moderate density of larvae. They can be reared on plant cuttings (Quercus sp). The third life stage is lime green with milky white stripes; the fourth life stage is yellowish to lime green with white spiracles, turquoise tubercules with red spines.

The fifth instar is rather unique – for it has a rather distinct blueish green color – a shade somewhere between cyan and mint green.

Once their development is completed, incredibly beautiful moths emerge from their cocoons. The males are bright orange, with stunning pastel colored eyespots. Females are yellow, with brown markings. These beautiful, ephemeral and lutescent animals only live for 7 to 14 days. In captivity, males and females mate rather easily and quickly; if left in a medium sized mesh (pop-up) cage with airflow.

On room temperature (21C), moths seem to emerge between 1 to 4 months most of the time, although this species is rarely every reared, so it is hard to be conclusive. Some breeders have attempted to diapause cocoons with moderate succes. If one wants to hiberate the cocoons, it’s recommended to keep them ‘cool’ but not ‘cold’; since winters in their native environment are gentle, and exposure to (near) freezing temperatures are likely to harm the pupae.

Females and females quickly paired up! A pairing was never observed (maybe it lasts for a short time or in the early morning?) but fertile eggs were produced from couples of moths from the same enclosure.

Thank you for enjoying my website about moths! Consider checking out our other pages – this website has over 100 moth life cycles for you to look at!

Thank you for reading my article. This is the end of this page. Below you will find some useful links to help you navigate my website better or help you find more information that you need about moths and butterflies.

Dear reader – thank you very much for visiting! Your readership is much appreciated. Are you perhaps…. (see below)

- Not done browsing yet? Then click here to return to the homepage (HOMEPAGE)

- Looking for a specific species? Then click here to see the full species list (FULL SPECIES LIST)

- Looking for general (breeding)guides and information? Then click here to see the general information (GENERAL INFORMATION)

- Interested in a certain family? Then click here to see all featured Lepidoptera families (FAMILIES)

Citations: Coppens, B. (2024); Written by Bart Coppens; based on a real life breeding experience [for citations in literature and publications]

Was this information helpful to you? Then please consider contributing here (more information) to keep this information free and support the future of this website. This website is completely free to use, and crowdfunded. Contributions can be made via paypal, patreon, and several other ways.

All the funds I raise online will be invested in the website; in the form of new caresheets, but also rewriting and updating the old caresheets (some are scheduled to be rewritten), my educational websites, Youtube, breeding projects, the study of moths andconservation programs.

Donate button (Liberapay; credit card and VISA accepted)

Donate button (PayPal)![]()

Become a member of my Patreon (Patreon)![]()

Find me on YouTube

Join the Discord server: Click here

Join the Whatsapp server: Click here

Facebook: Click here