Archaeoattacus malayanus, the Ancient Malay Atlas Moth, is a giant species of moth found in non Himalayan China: Yunnan, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, northern Vietnam, southern Laos, Malaysia, Brunei and surrounding countries. This species was split from Archaeoattacus edwardsii (White, 1859) in the past ; they were once considered to be the same species (they were split in the year 2010) . The main distinction here is that ‘true’ Archaeoattacus edwardsii is a Himalayan species found in the Himalayas in China, Nepal, and Bhutan and that all the non-Himalayan Asian mainland specimens constitute different species of Archaeoattacus.

What is the pinnacle of mythical species of silkmoth (Saturniidae)? Answers might vary since it is a little subjective. Many people would answer with a rare moon moth species; perhaps Actias niedhoeferi, Actias chapae or Actias rhodopneuma? Or is the giant comet moth (Argema mittrei)? Others might mention the hercules moth (Coscinocera hercules), or perhaps the long-tailed Copiopteryx species found in the rainforests of South America, or the tiny Eudaemonia species that look like fairies found in Africa.

But ‘Ancient Atlas Moths’ aka genus Archaeoattacus are up there too. In appearance they very much resemble the ‘true’ atlas moths (=genus Attacus). And indeed, their ecology is similar too, much like their appearance. However, there are a few fundamental differences. Genetically and morphologically the adults and larvae are distinct. Secondly, Ancient atlas moths (Archaeoattacus) tend to occupy the medium- to high- elevation forests that have more moderate temperatures while the genus Attacus tends to occupy the much hotter lowland forests, although there is some overlap (this, of course, is a huge generalization that may have a few exceptions since we are comparing many species here). Some Archaeoattacus species, like A. edwardsii have been observed up to 2500m in the Himalayas for example. It seems that in comparison, Archaeoattacus are better adapted to lower temperatures. And then, perhaps more superficially speaking, most true ‘atlas moths’ (Attacus) tend to have brown, chestnut to olive-green tones, while ‘ancient atlas moths’ (Archaeoattacus) tend to have a rather ‘purple’ish tone.

Sometimes, insect fanatics like to breed these moths in captivity. Generally speaking, Archaeoattacus species are not for beginners, since especially the more fully grown mature larvae have their sensitivities. While definitely challenging, the good news is that they are also not extremely difficult, and a lot of seasoned moth-breeders have managed to breed them in captivity. Perhaps just as challenging as rearing these moths is obtaining them in the first place. Females of each of the four Archaeoattacus species (edwardsii, stauderingi, malayanus, vietnamensis) can be rather elusive and only infrequently come to light traps. Not to mention the fact that the number of people who are willing to go to the most remote corners of the world just to find moth eggs, is… well, it’s not zero, but it’s probably not a very high number either. Therefore they typically remain a wish-lish species for many moth fanatics, that’s offered only once in a blue moon. As the author of this moth website, at the time of writing (2025) I have been breeding moths off and on for about 12 years, and it’s my first time, finally rearing Archaeoattacus!

In the wild, there are some records of the larvae feeding on Machilus (Magnoliaceae), Ilex chinensis (Aquifoliaceae), and Ailanthus altimissa (Simaroubaceae). Breeding Archaeoattacus malayanus is very similar to breeding Attacus species (such as Attacus atlas), in my personal opinion. The conditions and even food plants that can be offered are quite similar; a good choice for the larvae is tree of heaven (Ailanthus altimussaiaia), laurel cherry (Prunus laurocerasus), privet (Ligustrum)and ash tree (Fraxinus). Some reports also mention lilac (Seringa vulgaris) and poplar (Populus). Experience with breeding atlas moths will definitely make these easier. The main difference is that Archaeoattacus malayanus likes more gentle temperatures; do not blast them with tropical heat. A temperature of 18C or so seems great.

- Difficulty rating: Hard

- Rearing difficulty: 7.5/10 (Fro m egg to pupa)

- Pairing difficulty: 6.5/10 (Achieving copulations)

- Host plants: Interestingly, I can’t find much information about the host plants this species uses in the wild (!) but there are some records of the larvae feeding on Machilus (Magnoliaceae), Ilex chinensis (Aquifoliaceae), and Ailanthus altimissa (Simaroubaceae) that remain to be verified – in captivity it has also been reared on Prunus laurocerasus, Ligustrum ovalifolium, Ailanthus altimissa, Seringa vulgaris, Fraxinus excelsior, Populus sp., Ilex chinensis.

- Natural range: Mountains; medium to high altitude in non Himalayan China (Yunnan), Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, northern Vietnam, southern Laos, Malaysia, Brunei and surrounding countries

- Polyphagous: Quite polyphagous. Interestingly, I can’t find much information about the host plants this species uses in the wild (!) but larvae accept many plant families such as Rosaceae, Oleaceae, Aquifoliaceae, Simaroubaceae, Salicaceae, Altingiaceae and more.

- Generations: It seems to be double-brooded in the wild; with one flight in March-April and one flight in October-November. While moths in captivity can behave totally different from the ones in the wild, this actually-perfectly adds up to when my moths emerged in captivity!

- Family: Saturniidae (silkmoths)

- Pupation: Silk cocoon

- Prefered climate: Moderate to cooler temperatures, and higher humidity (it is a high altitude mountain species).

- Wingspan: 180mm-225mm. They are giants!

- Binomial name: Archaeoattacus malayanus (Kurosawa and Kishida, 1985)

- Special notes: Needs more gentle and cooler temperatures compared to Attacus species. Tolerates higher humidity than Attacus.

The eggs of Archaeoattacus malayanus can be incubated rather easily in plastic petri dishes or airtight food containers. Larvae generally hatch in 10 to 15 days time. The best food plant to use for this species is Ailanthus altimissa, or Fraxinus if it can be given fresh or replaced often (it does dry out quickly in some cases; they produce large adults. However, more often, in captivity the species is reared on Prunus laurocerasus and Ligustrum sp. with acceptable results as well. Some people have mentioned good results on Liquidambar, but for some reason, my larvae were reluctant to eat it.

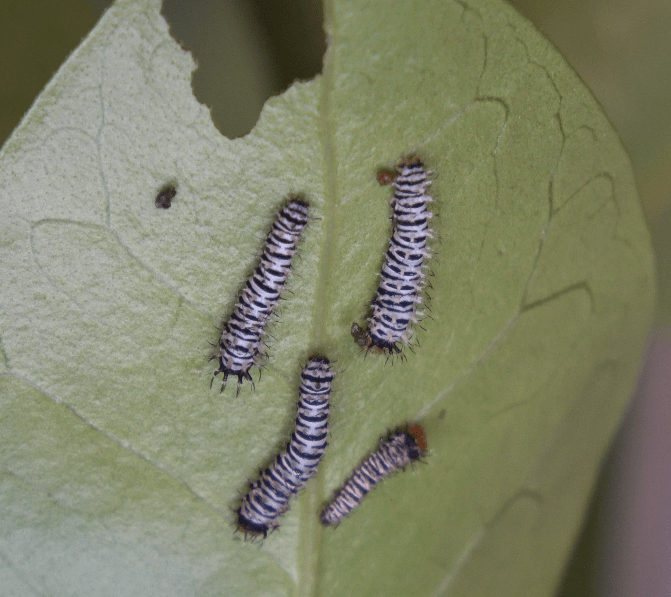

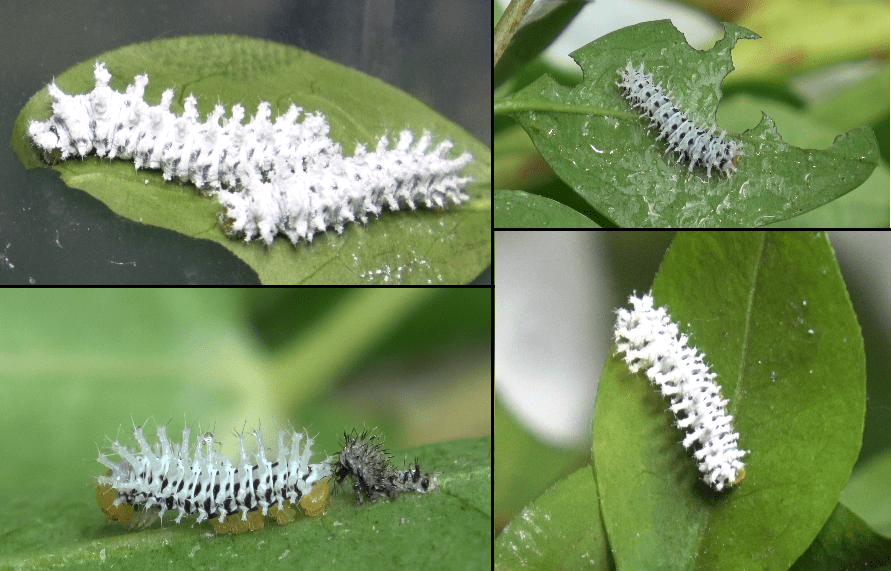

Rearing the first three instars is, in my opinion, quite easy and problem-free. The trouble generally starts in L4 and L5 (L6?). The first three life stages are however generally quite hardy and easily reared in plastic boxes.

Instar 1 through instar 3 are easily raised in plastic boxes, provided with the freshest possible leaves, and perhaps a supportive layer of paper towels to absorb excess moisture and make the enclosure easier to clean. From instar 4 and beyond things might get more tricky. Larvae start demanding more airflow; they generally don’t like ‘stale’ air. They can be reared in plastic boxes with ventilation grids or the lid removed. Or if the ambient conditions are good enough, simply in open (net) cages or laundry baskets. They can be kept in a relatively dry setup, so long as the relative humidity remains above average.

Host plant quality makes a difference too, although it is sometimes difficult to estimate how good an individual host plant is when given to larvae. A plant might look healthy but be more nutritionally deficient. Larvae tend to eat from the ‘tip’ of the shoots of the host plant, consuming the younger leaves first in some cases, as they go down the branch and consume the older foliage over time.

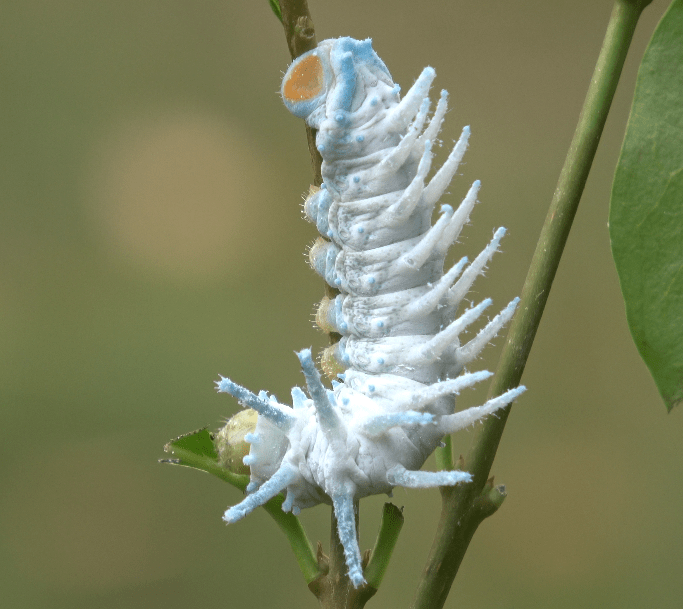

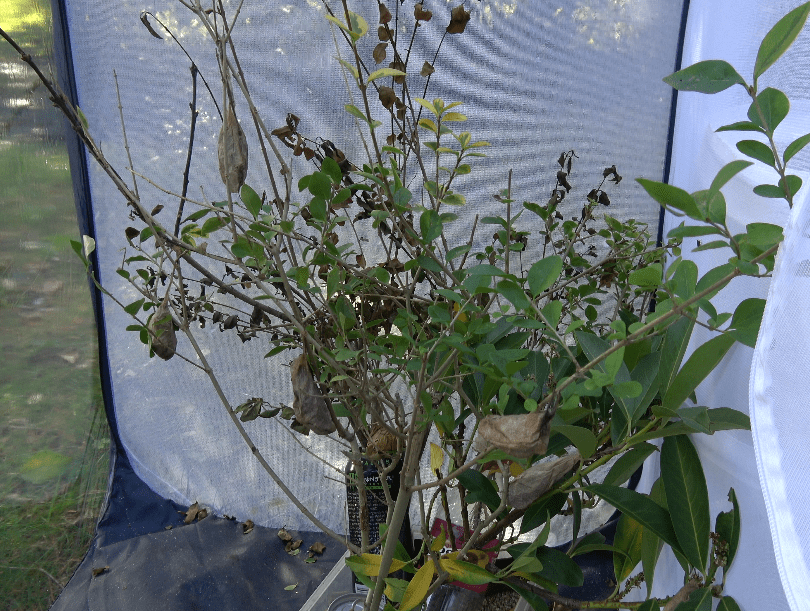

Once fully grown, the larvae of this species become quite chubby. I reared the L4 and L5 in open cages and laundry baskets, with cut branches of host plant placed in water to keep them fresh.

It is recommended to keep them in lower densities. Indeed, some entomologists have managed to raise large batches of larvae; with 10 to 20 individuals making it to cocoons inside one enclosure. I find this to be a bit risky. For sure these larvae are a bit sensitive to stress, and even worse, diseases. If one of them gets sicks, the probability is high that it will infect the rest! Seperating them into enclosures and keeping about 3-4 larvae per larger enclosure seems to work better. It lowers the risk of contagion and the larvae stressing eachother out.

The final instars are the most troublesome instars in captivity; at this point this is where they might start ‘dropping off’ in some cases.

Generally speaking, there are still a lot of unknown factors that will make or break your rearing of Archaeoattacus. Sometimes the larvae struggle to grow for seemingly no reason, even if you do everything right and by the book, and other times, they will grow well using nearly the same setup. I am hoping to rear this species more often in the future and hopefully study and identify the factors that are crucial for their survival rate and development.

With some skill and perhaps a bit of luck, your larvae will make it to cocoons. Larvae seem to gnaw at the branches until they snap before finally spinning a cocoon at the tip of said broken branch. The cocoon is tethered to the host plant and said branch with a silk ‘pad’ that extends down the twig (these ‘pads’ are comparable to the ones also often seen in a number of Antheraea species). The cocoons are rather oval, with a narrow tip and blunt bottom end, and consist of papery brown silk.

The pupae can be kept on room temperature. Humidity is important for the pupae. The species seems to have two broods a year in nature, one near April and one near October. In captivity they more or less seem to obey that pattern (although environmental cues can confuse moths in captivity, so do not be suprised if they don’t).

NOTE: My breeding method still needs improvement. This is important to know for the readers of my site, since they (you!) are taking advice directly from me. But it’s good to know who you are getting advice from. I ended up with about 9 cocoons out of ~40 or so eggs and larvae (the hatching rate was high). This moth is considered to be challenging to rear, so while I think this is an acceptable result and it qualifies me just enough to add this rearing article to my website; but it’s far from a perfect result. My rearing was definitely not a perfect, lossless rearing. So perhaps use the tips I would like to breed this species again in the future with less losses(!). If you have some advice for me, e-mail me! bart.coppens@hotmail.com

Finally, if you did everything right, you can expect to observe the incredible looking moths. Their dark, deep purple hues and golden wingtips are remarkably stunning. The moths are really quite large and generally have wingspans between 17cm and 22cm. Females are larger than males. High humidity is important during the emergence of the moths themselves; Archaeoattacus moths have a large wing surface area, and the process of inflating the wings and drying them takes a long time. If the air around them is too dry, the wings might dry prematurely before this process is finished, resulting in ‘wrinkled’ moths. If you notice any moths crawling out of their cocoon, it’s a good moment to spray or increase the humidity in the room somehow.

The moths themselves don’t seem as long lived; a modest 7-8 days seems to be the average lifespan. Females can make it to 10-12 days in some cases. Typical for a Saturniidae.

In terms of pairing, the species is not terribly difficult to pair, but it’s also not easy. Males and females are known to mate ‘naturally’ in captivity in some cases, especially when provided a large spacious enclosure, much fresh air and/or airflow, no stress (keep handling to a minimum) and no artificial light. They are a little bit more demanding than the average Saturniidae moth in this regard. And in some cases, it seems that some individuals just aren’t that interested in mating for reasons unknown.

The good news is that the species can also be handpaired! However, handpairing this species is also a bit tricky at times. It’s similar to handpairing Attacus moths, but they seem to be more susceptible to stress. Handle the male or female for too long, and they might not want to cooperate at all anymore. The best moment to handpair this species is in the evening, especially when the male starts to become active, and begins to show signs wanting to fly round in his enclosure. The best males to use for handpairing seem to be males that are about 2 days old; too ‘fresh’ ones tend to be disinterested in mating while too ‘old’ individuals sometimes have trouble shutting their claspers and staying attached to the female, or might have lost the tarsi on their legs which makes them freak out when they fail to grasp the female or the cage netting.

Special thanks: I would like to thank all the readers who have contributed over the years. This website has gradually developed hundreds of pages, with life cycles of some of the most elusive moth species in the world in high definition, and has hundreds of thousands of visits! – it is thanks to your support and the crowdfunding I have received that we can continue to rear moths and document their life cycles; a labour and time consuming process. I will continue to improve and update this website to the best of my ability. Usually I don’t explicitly mention these things on the pages of my website, but this species is really special; together with Actias neidhoeferi (Taiwanese Moon Moth) it is perhaps one of the rarest and most mythical species I have managed to rear and write about thusfar. Your reading, sharing, and yes, donations in some cases have allowed this website to grow and thrive! Special thanks to: Roberto Cardona / John Metcalfe / Kimberly Karn / Ingrid Singh (some of my top sponsors/patrons of all time!), and everyone who has been reading, sharing and engaging over the past few years. Some of the older pages of this website will be rewritten over the years and modernised too.. give me time!

Thank you for reading my article. This is the end of this page. Below you will find some useful links to help you navigate my website better or help you find more information that you need about moths and butterflies.

Dear reader – thank you very much for visiting! Your readership is much appreciated. Are you perhaps…. (see below)

- Not done browsing yet? Then click here to return to the homepage (HOMEPAGE)

- Looking for a specific species? Then click here to see the full species list (FULL SPECIES LIST)

- Looking for general (breeding)guides and information? Then click here to see the general information (GENERAL INFORMATION)

- Interested in a certain family? Then click here to see all featured Lepidoptera families (FAMILIES)

Citations: Coppens, B. (2025); Written by Bart Coppens; based on a real life breeding experience [for citations in literature and publications]

Was this information helpful to you? Then please consider contributing here (more information) to keep this information free and support the future of this website. This website is completely free to use, and crowdfunded. Contributions can be made via paypal, patreon, and several other ways.

All the funds I raise online will be invested in the website; in the form of new caresheets, but also rewriting and updating the old caresheets (some are scheduled to be rewritten), my educational websites, Youtube, breeding projects, the study of moths andconservation programs.

Donate button (Liberapay; credit card and VISA accepted)

Donate button (PayPal)![]()

Become a member of my Patreon (Patreon)![]()

Find me on YouTube

Find me on Instagram![]()

Join the Discord server: Click here

Join the Whatsapp server: Click here

Facebook: Click here

The life cycle of Archaeoattacus malayanus is rarely revealed or exposed! But entomologist Bart Coppens has done it today in 2025. Enjoy!